I spent the better part of Summer 2013 as an exchange student in the city of Bandung, in Indonesia. Contrary to the better known (to Westerners) vacation spots in Bali, Bandung is not a coastal town, but a city deep in the volcanic highlands of West Java.

At almost 800 meters of altitude, the region in which it was built had a cooler climate that made it ideal for tea plantations. During the colonial period, it quickly became a favored resort city for Dutch East Indies Company officials, with a number of luxury art déco hotels, cafés and boutiques that earned it the nickname of Parijs van Java – the Paris of Java. In fact, it was so beloved and glamorous that in the 1920s the Dutch intended to move the East Indies capital from Batavia (now Jakarta) to Bandung.

These plans never came to fruition due to the start of the 2nd World War, which materialized in the form of a fulminant Japanese invasion in 1942. Initially greeted as liberators, the Japanese eradicated the Dutch colonial administration. Their foreign policy, marketed as “Asia for Asians”, included fostering nationalist organizations that would collaborate in the struggle against European rule. Many of the heroes of Indonesian independence, like Sukarno and Hatta, started their careers in Japanese-sponsored organizations.

The end of the war was seized as an opportunity by these Indonesian nationalists to declare independence. The Dutch, who were on the victors’ side, had only preserved a testimonial presence in Java, and upon Japanese surrender the territory had fallen under the formal control of the UK-led South East Asia Command on August 15th, 1945. The Japanese still retained around 300,000 troops and civil servants in the East Indies, and an odd situation developed when the British had to rely on their former enemies to organize and secure the reoccupation of territories.

The following four years were spent in vicious fighting between Indonesian nationalists, armed and trained by the Japanese, and the British authorities who were trying to win back the East Indies for the Dutch. The Japanese personnel that remained in the island was left in an ambiguous position. Many actively followed their country’s official policy of assisting the British, while others abandoned their arms and supplies to the Indonesians and in some cases even went native and joined the revolution.

A lot of these battles happened in and around Bandung. In March 1946, British Major General Douglas Hawthorn issued an ultimatum for Indonesian forces to evacuate South Bandung. Indonesian troops and civilians left en masse, not before burning down the city and dynamiting infrastructure. The event, witnessed by an Indonesian journalist from a nearby hill, was named Bandung Lautan Api, the Bandung Sea of Fire. It quickly gained symbolic significance as a revolutionary gesture, immortalized in songs and still commemorated today.

I remembered this famous historical episode as I gazed upon the city from a hill in the outskirts one August evening. The Bandung I was watching seemed to be on fire, too. The equatorial night was busy as street food vendors served up sizzling nasi goreng and chicken sate. The air was thick with the sweet-spicy scent of clove cigarettes and the smoke of bonfires burning on stone sidewalks. There are no seasons in the equator, and dead leaves accumulate on the ground throughout the year. Mingled with discarded styrofoam dishes and plastic wraps, people burned them to keep the sidewalks walkable.

The history of Bandung as an icon of decolonization didn’t end in 1946. Independence finally came about in 1949, and the newly minted republic immediately started its experiments with parliamentary democracy, presided by Sukarno. The young nationalist leader had developed the core tenets of his political philosophy as an architecture and civil engineering student in the Bandung Institute of Technology. Now, he was ready to put them in practice: Republican Indonesia was to reject traditional Javanese feudalism and replace it with a contemporary vision, inspired by a kind of Third World socialism avant la lettre. Modernity was clean and elegant in style, educated, prosperous and anti-imperialist.

As all architects who achieve a measure of power, Sukarno soon evolved into a more authoritarian figure, staying in power until his ousting in 1967. The new decolonized world, which the Republic of Indonesia had spearheaded, was still undefined and in turmoil, more so with the growing distrust between the USSR and the US. There was an opportunity to build a third geopolitical sphere, in tune with the intensely modern principles that were being attempted in the archipelago.

Newly declared republics sprang up every other month, with the urgent need to insert themselves in the context of global confrontations. In 1955, Sukarno organized the Bandung Conference, which invited representatives of twenty-nine African and Asian countries, most of them of recent creation. Together, the assistants represented more than half of the world’s population, which at the time was around 3 billion.

The conference was conceived as a call for racial equality, economic and political cooperation among the newly independent nations of Asia and Africa, and a rejection of colonialism, imperialism, and racism. It is funny to consider that all these elements were to become, decades later, an enthusiastically enforced official State ideology for most of the political systems the Conference sought to defeat.

The Bandung Conference laid the groundwork for the formation in 1961 of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), which nowadays includes 120 countries. That’s still equivalent to around 60% of the world’s population and growing, unless demographic trends are strongly reversed (hint: they will not be).

Luckily for potential imperialist adversaries, the Non-Aligned countries do not align much with each other. The club includes members with views as radically different as Afghanistan, Colombia, Vanuatu, Belarus and Senegal. Sometimes these differences reach near faultline status, such as the open chasms between Iran and Saudi Arabia or between India and Pakistan.

The last NAM summit before the pandemic was held in October 2019. The chosen venue was Baku; the capital of Azerbaijan reflects the recent successes of the country’s foreign policy and caviar diplomacy. Still basking on his 4th electoral victory the previous year, President Aliyev made the opening speech, once again promising to uphold the principles of the Conference of Bandung: self-determination, non-interference, equality, respect for sovereignty, and non-aggression.

Ten months later, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict was reignited with impressive results for the Azeris. The war in Ukraine has only made things better, as the sanctions aimed at Russia open a wide field of opportunity to Azeri fossil fuel exports. Azerbaijan, which many EU citizens can’t properly locate on a map, is likely to strike gold by preying on European energy insecurities. Gold that will reach Russian pockets anyway, since like half the Azeri gas industry owned by Lukoil.

But let us not digress. Much like Azerbaijan, Indonesia is enjoying a golden epoch, thanks in part to Russia’s fall from grace. Indonesia is a prime supplier of thermal coal and nickel steel, which have seen soaring prices due to the war. This, coupled with reactivation of travel and the end of covid restrictions, spurred its GDP growth to a whooping 5,3% last year. The island nation is likely to become the world’s 5th economy this decade, overtaking the UK, Germany and Russia. It’s even starting to make moves in Africa.

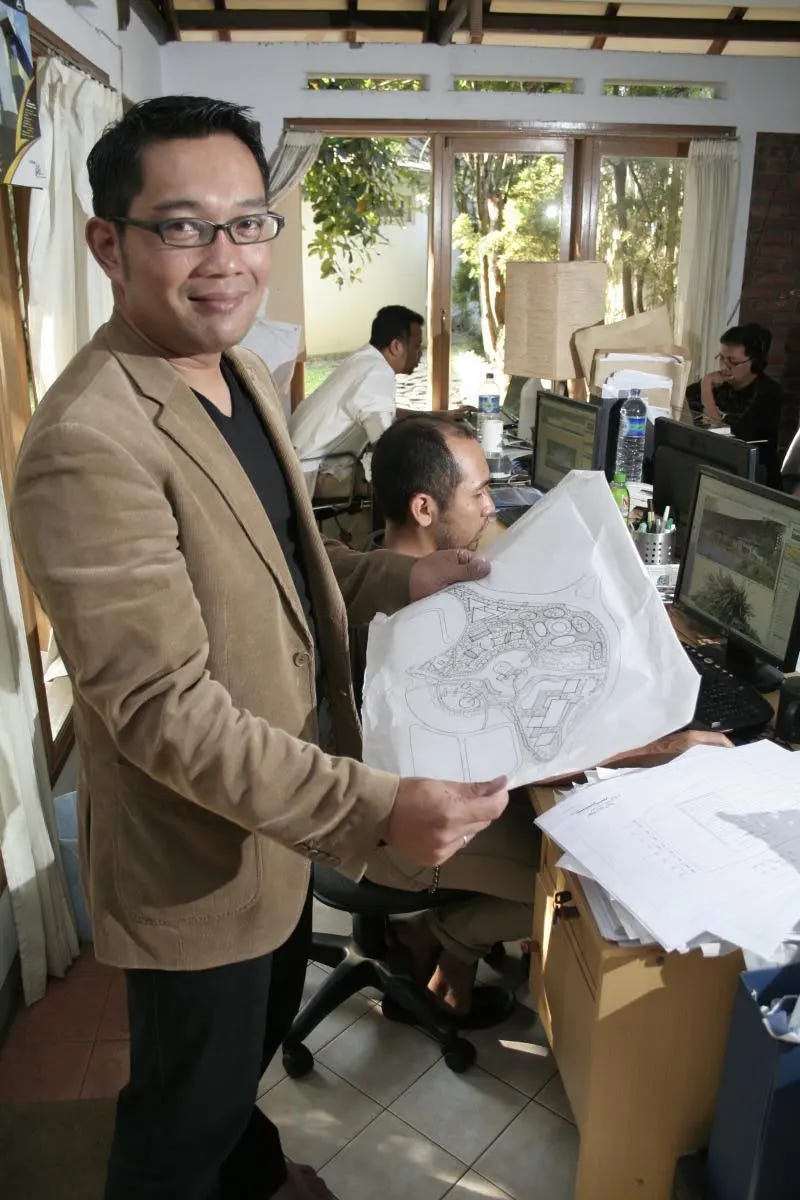

Bandung has changed a lot since my visit ten years ago. Shortly before my arrival to the city in June 2013, a new mayor was chosen. Running as an independent, Ridwan Kamil represented a younger generation, concerned with corruption and climate change. Just like Sukarno, Kamil graduated as an architect from the Bandung Institute of Technology. Having spent time in New York, California and Hong Kong, his vision for Indonesia is also of a clean and elegant modernity.

Under his mandate, Bandung built green spaces, regulated traffic, improved transportation and banned styrofoam packaging from street vending, going on to win the clean air award from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. Kamil, who has millions of followers on social media and frequently makes cameos on TV-shows, has seen his popularity soar in the last decade and is now governor for the West Java province. He is also making a run for the Vicepresidency in the general election of 2024, although there are rumors that his mind is on eventually becoming President.

Meanwhile, the Yes-Aligned world is enjoying the fruits of conflict. Some forecasters argued that, with the end of the Cold War, the peripheral countries of the Third World would have to redefine their foreign policies to adjust to the New Order. Perhaps they did not think that it might very well be the other way around.

I plan on going back to Bandung as soon as I get the chance. When I do, it’s likely there won’t be any bonfires nor dynamite that set the sky ablaze for me, other than the glistening peace of city lights.

Will share this one with my readers soon enough.