At the beginning of this year I found myself in Lagos, Nigeria, on an urgent, flash business trip. The moment was less than ideal for traveling, as it was just a few days before the historic February 25 general election that made Bola Tinubu president-elect. Political tension was at its peak, and I was strongly advised not to visit the certain areas. Not to visit the country in its entirety, in fact, if I could avoid it.

The prospect excited me. I was expecting to scrounge a few hours to explore the glamorous coastal city. A lot of the things that make Nigeria dangerous happen in the Northern, lawless regions of the country. The permanent threat of jihadism is perhaps the best known one: terrorists have killed about 40 thousand people there since 2009. Pervasive banditry of the non-ideological kind is also a huge problem and adds a few thousands to the country’s violence-related death toll.

Lagos, the former capital, is not exempt from the scourge of criminality and violent robbery, of which clueless tourists are a favorite victim. Since I couldn’t possibly pass for a local, I decided it was not the time for me to brave the streets. Of the 18 hours I was to stay in the country, I spent roughly 6 sleeping and 6 queuing at the airport, which left me 6 hours for work and rest at the hotel.

It was a modest, 3-star airport hotel, belonging to widely-known French chain. I had chosen it because it aroused in me feelings of familiarity and warmth, as it reminded me of childhood road trips with my family across Europe. I was not disappointed: the brand was more or less preserved in these latitudes.

A small difference grabbed my attention. In Europe, you see small placards in hallways and elevators that remind guests to save water and be as eco-friendly as possible. These signs explain with exhaustive detail the many things that can be done with the water you save by re-using a towel, and the green measures the hotel has adopted.

The Lagosian version of these placards warned that prostitution and sexual exploitation of minors would not be tolerated on hotel grounds, and asked guests to report any suspicious activity to staff. The hotel had developed a protocol against human trafficking in collaboration with the government for this specific purpose.

This state of affairs is not surprising at all to those familiar with intercontinental migration dynamics. At the height of the Mediterranean migrant crisis, in 2016, more than 35,000 Nigerians made it to the Italian shores. A quarter of those were women, a staggering 80% of which was destined to forced prostitution.

Well-structured criminal networks as the ones described in this post, however, do not employ the maritime route through Libya. They bring the girls by plane, normally through tourist visas and family reunification. Air routes are faster and bring the women in a better condition, which makes them more profitable.

It's easy to imagine that these are massive, complex international operations. The intricacies of human trafficking across the Mediterranean are already known by long-time readers of this blog. The story of how the best-established Nigerian networks were formed is, nonetheless, quite interesting.

Nigeria and Italy do not have much of a common history nor a shared language. The colonial past that ties Nigeria to its diaspora in the UK doesn’t exist. According to some reports, the seeds were planted in the 1980s, when it was fashionable for Italian oil workers from Agip and Italian Petrol to bring home the local girlfriends they had met while working in the oil fields of Nigeria.

Alas, love is fleeting. Some women who stayed in Italy eventually left the men and made a living through various means, like small jewelry shops and agriculture. Nothing quite as lucrative as becoming a maman, though: facilitating the immigration of younger compatriots in exchange for an interest paid through sex work.

The story is not very original: the maman offers transportation and the documents needed to work in Europe. The victim agrees to pay back the expenses of the trip with her soon-to-be-acquired job. On arrival to Europe, the job is revealed to be streetwalking. Usually, the debts are north of 30 thousand euros. The usual rate per trick is about 15 euros. We leave the math to the reader.

There is a lot of psychological manipulation involved, of course. The agreement is formalized by folk magic rituals performed by respected local figures. It’s not unusual for the environment of the victim to be aware of what’s going on, and even to sponsor the trip and participate in the profit. Although the women may be guilt-tripped into accepting the deal, it’s likely that they don’t fully know the conditions awaiting them in Europe. The glamorization of the escort lifestyle through Nollywood films on Netflix probably does not help the girls’ assessment of risk.

Originally, the mamans traveled to Africa looking for suitable candidates and used local connections to arrange the direct flights from Lagos to Rome. After members of the Italian embassy in Lagos were charged for facilitating this in 1999, the route became much harder, and other European airports like Madrid, London and Amsterdam became preferred entry points.

With this complication of logistics, operations became more sophisticated and Nigerian crime fraternities became involved in all parts of the process. Organizations like Black Axe and the Supreme Eiye Confraternity, spread all over the world through the Nigerian diaspora, started managing the recruitment and the immigration process. Acting in various capacities (recruiter, protector, smuggler), they are the link between the sponsors in Nigeria and the mamans in Europe.

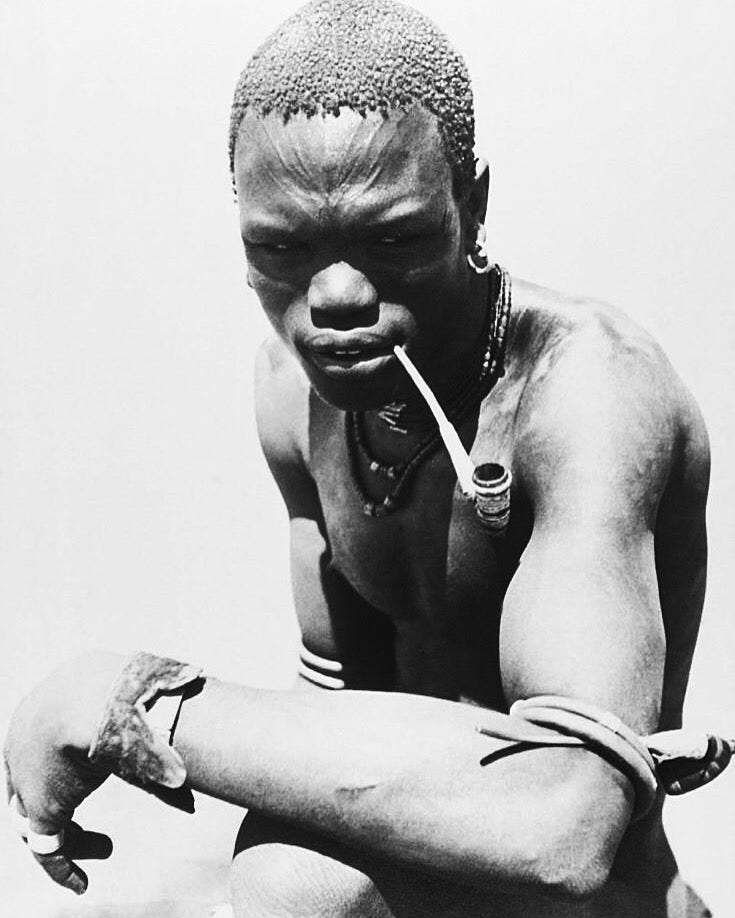

The Nigerian mafia has an interesting origin story of its own. Most fraternities directly descend from 1970s radical student movements, to which they owe their name. According to the Supreme Eiye Confraternity Facebook page, for example, their mission is “to uphold the core nature of the African culture with a commitment to excellence" and "to make [a] positive impact on the socio-political psyche of Nigeria and ensure complete break away from [the] colonial/imperial cultural domination of the time”.

It’s exactly what it says on the tin. The regression to animist and occult traditions makes these secret societies look like Pagan societies of Antiquity did: mysteric, Machtgelüst-based, violent and hierarchic. Allegedly, struggles for prominence are vicious, and dominance in the Männerbund is established daring acts of bravery and brutality.

The organizations still maintain a presence in Nigerian campuses, even though their founders finished college long ago. Naturally, because these boomers currently hold power in Nigeria, it’s safe to assume that the mafia is heavily intertwined with government elites, especially since not that many people go to university there.

As you’d expect for a bunch of magical Black Panthers, these crime networks are very secretive and enshrouded in mystery. This is fundamental to their power: the collaboration of the trafficked women is ensured through voodoo ceremonies, in which sponsors take away blood or pubic hair from the victim as a safeguard for compliance. These juju curses act as the essential spice in the extorsion formula, while the fluid communication between the traffickers abroad and at home does the rest to keep the machine well-oiled and working.

It is worth mentioning that the legal measures taken in Europe during the Mediterranean crisis were not particularly effective. EU Directive 2011/95 basically nullified illegal stay as a felony, which means that asylum claimants cannot be expelled from the country until a firm resolution. The average processing time for applications is around two years, which is quite practical for the traffickers, as the girls can be exploited during the whole time. The costs of the operation are lowered since housing is provided by local government, and anyway few women remain profitable after two years: they either break down or find a way to break free. This has led crime syndicates to encourage asylum claims, even providing the lawyers for it.

All in all, it’s a very sad affair. An interesting omission of all the NGO reports I had to read for this article is how the enforcement of border controls and immigration laws would probably reduce the problem, but I guess that discussion is already trite enough for the sophisticated readers of this blog. The story perhaps works best as a case study for how Pagan revivals look, so hopefully those who must live a certain way will have taken notes.

A very impressive article!