Prometheus the Fire-Bringer and Pandora the extraterrestrial sex doll

We don't usually go out looking for myths: myth finds its way to manifest itself to us, an operating force that sheds light on the structure of the collective mind. Myths make understandable many elements of culture that would otherwise go unnoticed. This is why we believe myths are eternal, sacrosanct works. Their nature provides a security net for exploring the depths of shared attitudes and beliefs. Being removed those past events that are under understood as belonging to History, one can safely tread the shadows of culture with myth as a guiding light.

Myths cannot be understood as folk tales either. They are not popular, entertaining stories that have casually survived to present times, they don’t provide useful information on the life and customs of the Ancients, and they cannot be instrumentalized as arguments in current ideological conflicts. That’s why feminists sound somewhat comical when speaking about misogyny in Ancient Greece, using Greek myths as proof of the millennia-long oppression of women: a rhetoric adopted, ironically, by anti-feminist activists, who value this supposed oppression positively and fancy themselves reactionaries.

In his Works and Days, Greek poet Hesiod (8th century BC) introduces us to a figure the feminists love to rally around: Pandora (literally Πανδώρα - “all gifts”), in whom they see a symbol of female unity against the Patriarchy. In the myth of Prometheus, Pandora is the first woman, made from clay and given to Mankind in retaliation for the Titan's transgressions. Pandora releases into the world all kinds of “sorrow and mischief” due to her curiosity. Hesiod gives another version of the myth in his Theogony, leaving her unnamed but describing her as the first woman, from whom came all those of “the deadly race and tribe of women who live amongst mortal men to their great trouble, no helpmeets in hateful poverty, but only in wealth". Those who find in Pandora’s myth an essay on the sexes, of course, tend to see Hesiod as “an oppressed representative of the agrarian middle class, socially subordinate to the powerful continental landowning nobility who sees the woman represented in the figure of Pandora as an economic inconvenience”. In other words, a Social Justice Warrior.

Pandora has only been given attention in recent times, Prometheus being the main character of the story for his connotations as protector and savior of Mankind. There was no translation of the myth into Latin until 1470, a fact which contributed to a slower diffusion of the meme. Nonetheless, the main factor in preserving Prometheus’ preponderance over Pandora is probably the hegemony of Christian culture. In such a worldview, Prometheus was primarily a Christ-like figure, who sacrificed himself to bring light to Mankind. His punishment (having his liver eaten by an eagle), was seen as analog to the spearing of Jesus’ side in the Cross. As an archetype, Prometheus stands in contrast to his brother Epimetheus, dreamy and foolish, who fell in love with Pandora and who cared more for animals than for Men. Interestingly, the names of the two brothers mean literally “first thought” and “after thought”, alluding perhaps to the ever-deteriorating quality of the Human race.

The fundamental transmutation of the myth into modern interpretations came with Italian priest and libertine Giambattista Casti (1721-1803), who first decided to replace the benefactor of humanity that was Prometheus with a new heroine: Pandora. Casti needed the character for his Novelle Galanti, stories designed to be read aloud to young ladies. To deliver his own version of the myth with greater effect, the priest resorted to the literary technique of the “found manuscript”, basing his novel in a made up ancient text unknown to the primitive sources. Casti’s light-hearted narration turned the myth into a breezy tale of the Italian settecento, full of erotic elements that tended to turn Prometheus more and more into a “suffering husband” archetype.

Goethe (1749-1832), who was more or less contemporary to Casti, also lost interest in Christianizing Hellenic myth. He wrote a Sturm und Drang poem as a twenty-something year-old, giving voice to Prometheus: he portrayed him as the friend of Humanity and founder of culture, who taught Men how to use fire to trick the gods out of the best pieces of sacrificed animals. By 1807, however, the German had also turned his attention to Pandora. In an unfinished theatrical piece titled “Pandora, ein dramatisches Festspiel”, sympathy for Prometheus is transferred to Epimetheus, the lyrical admirer of a fleeting and divine Pandora, source of joy and salvation, and herald of a new age of sensibility. Prometheus is even shown as unable to appreciate Pandora for anything else other than her beautifully built complexion, feeding into the trope of male lustful shallowness.

The Woke version of the myth (in both its feminist and anti-feminist variants) is of course an heir to the post-Enlightenment interpretations of Casti and Goethe. As a meme, it finds an apt environment for reproduction in the longhouse culture of Star Wars spirituality, Marvel super-heroism and Sex & the City anthropology. Lacking its depth, woke memes cheaply outbreed the hesiodic narratives. There is no intrigue for how life was really like on Earth before Pandora, when it was inhabited by Men-like creatures, obviously non-Human, who existed in painless harmony and peace. That the Poet might have not even considered the arrival of a woman as the source of sorrow does not even cross the Wokester’s mind.

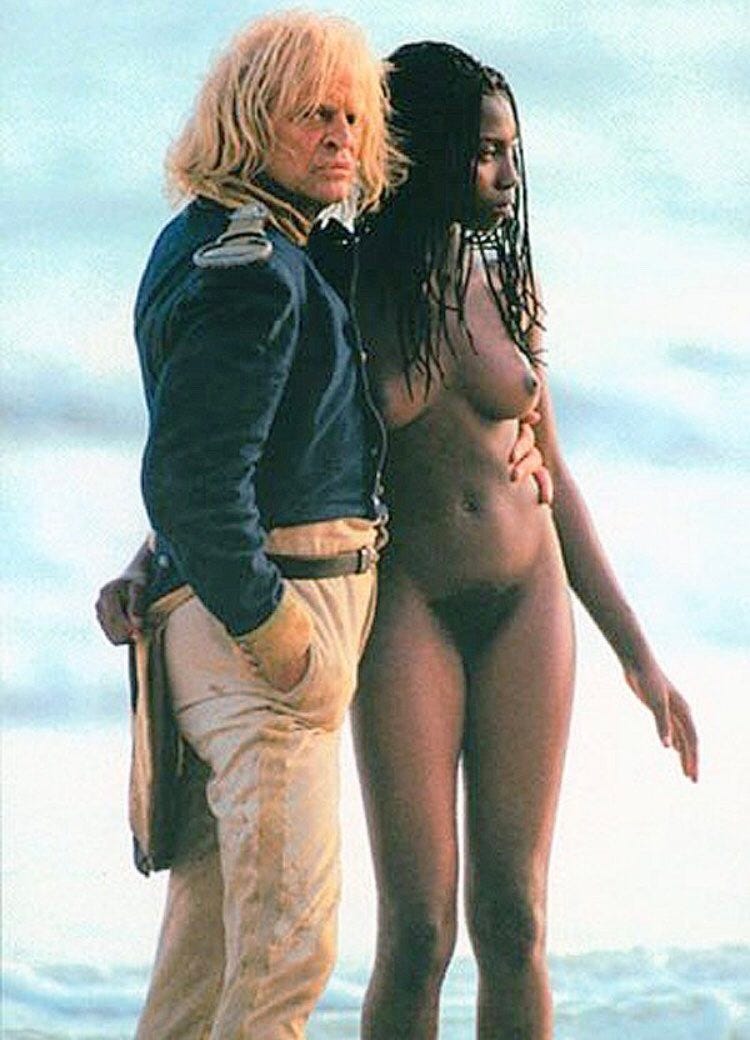

Pandora is sent by Zeus with a mission: to punish men, who had accepted from Prometheus the fire stolen from the gods. For this purpose, she carries a box, the contents of which she does not know. Unable to repress her curiosity, she removes the lid of the recipient, leaving all the misfortunes contained therein free to ravage the world of Men. The essential element of the hesiodic myth, however, is not Pandora’s feminity, but her nature as an instrument in the hands of the gods. An artificial being, harbinger of a new era: the Silver Age, populated by men of a race which spent a hundred years as children, only to suddenly become adult and immediately die. Pandora is not begotten but assembled by the gods: an extraterrestrial entity whose beauty and thoughts escape Man’s understanding. Thus, she does not represent the Feminine, but that which is fearsome, external and alien.

Instead of this, the Gospel of the Enlightenment has developed a crush on Pandora, just in case she could be that australopithecine female named Lucy. There is no interest given to the fact that Pandora could be not just a woman archetype but an Oracle of Destruction, heralding the arrival of the successive races into which Mankind degenerated: from Gold to Silver, Bronze, Heros and Iron. To the total disappointment of progressives and PUAs worldwide, Hesiod does not dedicate a syllable to explaining the differences between the sexes. Trapped in their memetic cave, they can’t understand that what piqued the interest of the Hellenic poet are the differences between men and gods, the ambiguities of humanity, injustice, the contrast between what is natural and what is artificial. Due to the Enlightenment's appropriation of the myth, we’ve stopped inquiring about the origins of knowledge. We inhabit a culture unable to ask about nature, truth, beauty, goodness and justice: a culture who finds the most promising application of Artificial Intelligence is the creation of interactive sex dolls.