War and Mass human sacrifice

On the initial days of my military life, one of the most common exhortations my section’s drill instructor directed to us was to remain at all times firmes como pollas (“stiff as cocks”). The soul needed to be tempered in the hot August sun to accomplish the necessary transformation of its metal, and graphic eloquence was just another tool.

Turning civilian university graduates into military officers was complicated for the instructor: post-graduate cadets generally lack the pliability of 17-year-olds fresh out of high school. A lot of early induction into military life has to do with cultivating simple virtues: punctuality, courtesy, tidiness. Virtues often unlearnt in college, which the instructor had to reinstill in us, the recruits, by way of inspiration, or fear of reprisal.

Failure to conform was swiftly punished; pressure was applied constantly by enforcing high standards on seemingly trivial tasks. Eventually, failure would always occur in the form of a loosely tied boot, an insufficiently clean rifle, a one-minute delay to roll call. This was by design: the instinct to elaborate excuses, learnt in childhood, had to be completely purged. The point was to fail, but never yield to self-indulgence.

In fact, apologies were strictly and explicitly forbidden. Often, when errors were committed, instructors temptingly offered the chance for an explanation. This was almost always a trap: smart cadets quickly learnt that answering “No excuse” went a longer way in softening disciplinary action.

It’s a small lesson that translates well into a disciplined lifestyle, and into a military officer’s career: the crucial and delicate difference between cause and justification is never more important than in a dispassionate study of violence. Conflict has intelligible causes that can be explained. Those who fight have their reasons. It doesn't mean they are Just (as in ‘righteous’) reasons.

Human sacrifice in antiquity was done in the name of a greater good: to summon rains, to appease the gods, etc. It probably didn't go always as planned, and if the desired answer was not obtained, the typical response would be to make more sacrifices until results were achieved.

Let's consider for a moment that human sacrifice had indeed always worked as expected: the blood of a handful of war captives was shed in exchange for a productive harvest, so that the people did not starve. This would be, after all, just a maximization of happiness. Maybe the Aztecs were nothing more than proto-Utilitarians; colorful, violent predecessors to Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill.

To condemn human sacrifice while accepting this idea is usually achieved by attacking the religious beliefs that justified the killing. In other words: Aztec human sacrifice was wrong because it was done in the name of non-existing, made-up deities. There was no identifiable connexion between the blood ritual and the protection of the polis (or so it would appear to the casual, agnostic observer).

[There’s a problematic corollary to this: would human sacrifice be justified in the name of existing, non-made-up deities? Perhaps we can address this later.]

But the perversion that human sacrifice entails lies not in that it is "unreasonable" or "superstitious". It's wicked because the guilt is hidden among the collective. What’s more: the murder is taken without personal risk, since the victim is defenseless, and sometimes even voluntary.

This second reading interprets human sacrifice as a commodification of a sacred object (human life) in exchange for a perceived benefit, usually to be enjoyed by the collective. Its immorality lies on its wrongful use of what is holy, and not in its erratic results or unexplainable mechanisms. This is what scandalized the Spanish newcomers, men for the most part no stranger to violence, death or even superstition. What they saw in the apex of Tenochtitlan’s temples was not stupidity, or even unintelligibility, but the debasement of Humanity for the appeasement of demons.

Neither Mexico nor the wider world have changed much in this practices. Ask any cartel member. Wars over geopolitical imperatives, and especially wars over control of resources (cocaine or oil, it doesn’t matter), are explained better as the appeasement of demons.

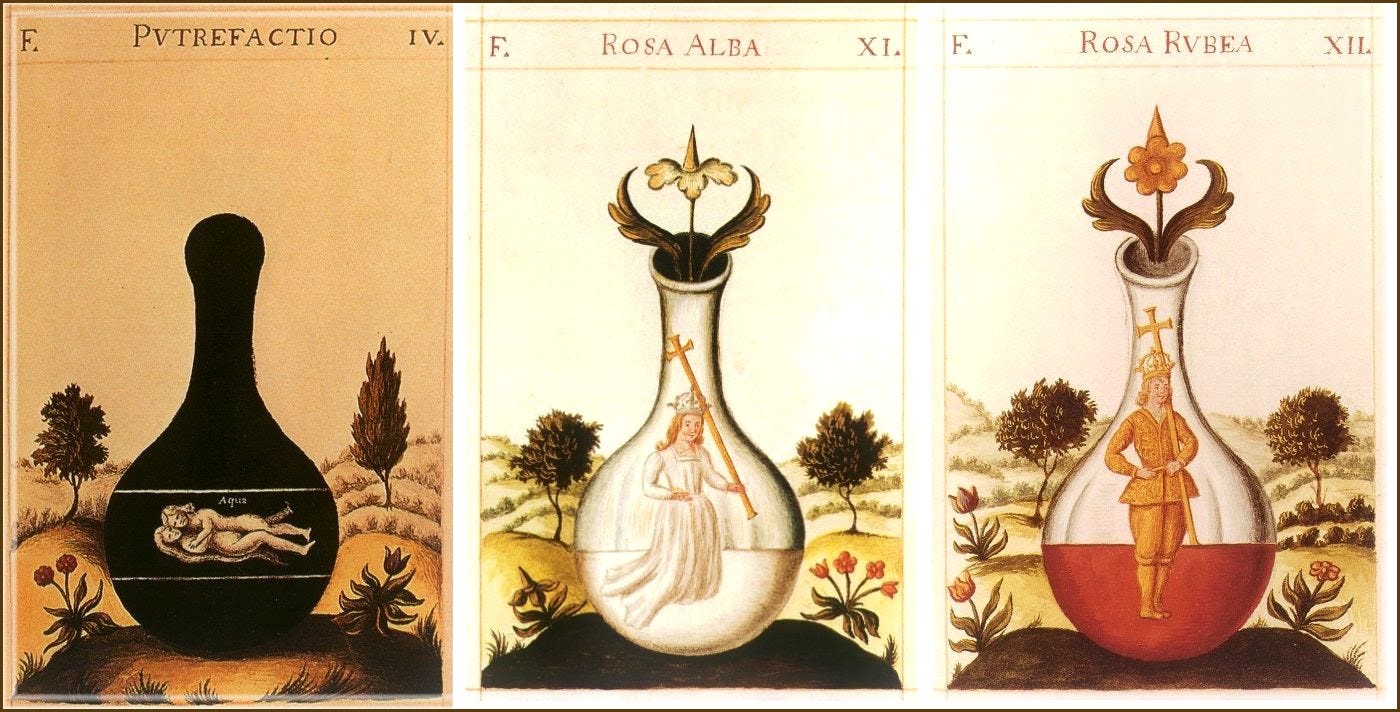

We have already established that explanation is not justification. In this case, the explanation would be something similar to this: your wealth is stolen, so you assign it a price in blood. Ideally, you buy it back with the enemy's blood. Sometimes, you have to add a bit of your own too. Whatever the case is, even if the stolen wealth is irretrievable, at least somebody payed for it. The constant here is the cyclical transformation between blood and gold.

In antiquity, those who engaged in resource warfare had something to gain. There was always a chance for loot or social ascension, so the moral calculation was deeply personal: you went raiding, robbed cattle and wives, got rich and famous; with the ticket also came the risk of having to pay in blood. This was the ethos of the Vikings, now so much en vogue: an attitude that did not distinguish war from criminality, not at all different from the lifestyle glorified in gangsta rap. It had little to do with punctuality, courtesy, tidiness, or resisting self-indulgence. It was, however, sincere: a wretched, but not perverse, existence.

But what about modern wars for resources? Does the average citizen benefit from his country's power? Well, maybe he does: lower prices, increased maritime security, leverage in trade... These are the values Empires fights for. But when you play this game of arithmetics, then you have to ask how much blood is that benefit worth.

Just as in human sacrifice, in modern (ie, “democratic”) war, the prize of victory and the guilt of the crimes are all shared and diluted within the collective. The drone is just the culmination of this depersonalization. The target is blown to bits by an algorithm! Doom arrives not through magic formulas expressed through frenzied religious chants and drums, but encased in coldly silent silicon.

Responsibility for the crime is untraceable to anybody in particular: at best, some faceless schmuck in a container sitting in an air base in Nevada, sunlight-deprived and stripped of glory. The blood cost however, can never be shared: a victim is, foremost, a person.

Human sacrifice is evil not because of the barbaric ignorance and violence involved, but because of the perverse nature of the transaction: somebody loses everything, so that, in the best of cases, everybody gains something. In most cases, it’s not even everybody, but just the high priests doing the sacrificing.

This dark alchemical transformation of distinct personal blood into indistinct, allegedly collective wealth is precisely what makes modern resource wars a performative ritual of mass human sacrifice. And, like human sacrifice, these wars can be explained but not justified. You don’t appease demons: you cast them out.